by Sandra Mizumoto Posey

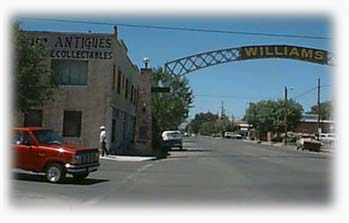

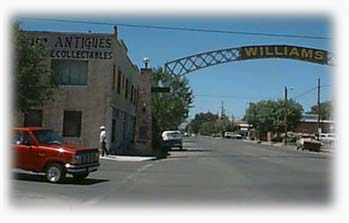

José Sandoval emigrated from Mexico six years ago and he's made Williams, California his home ever since. There are about two thousand people living in this little town just off Highway 20. I live in Los Angeles, where one populous suburb runs into another until expansion halts at the ocean's edge, so it's often difficult for me to remember that small communities even exist in our state. Williams can only be described as sleepy. The dust from the surrounding fields seems to float through the streets and coat the buildings with softness. The light is under a perpetual muted filter despite the relentless heat.

José Sandoval emigrated from Mexico six years ago and he's made Williams, California his home ever since. There are about two thousand people living in this little town just off Highway 20. I live in Los Angeles, where one populous suburb runs into another until expansion halts at the ocean's edge, so it's often difficult for me to remember that small communities even exist in our state. Williams can only be described as sleepy. The dust from the surrounding fields seems to float through the streets and coat the buildings with softness. The light is under a perpetual muted filter despite the relentless heat.

José's twenty now, and he gets by just fine doing agricultural work in the fields and occasionally applying his knack for working with machines. In his spare time he works on his car and hangs out with friends like Fernando Valdez, who he's known since High School. Fixing up his car is something of a burgeoning obsession for José, and he apologized sheepishly for the current dirtiness of his vehicle as I snapped away.

José's twenty now, and he gets by just fine doing agricultural work in the fields and occasionally applying his knack for working with machines. In his spare time he works on his car and hangs out with friends like Fernando Valdez, who he's known since High School. Fixing up his car is something of a burgeoning obsession for José, and he apologized sheepishly for the current dirtiness of his vehicle as I snapped away.

José taught himself glass etching and says it's all a matter of practice. He plans to add other designs to his car, but he's busy enough these days responding to the requests of friends like Fernando to do the same to their vehicles. It's a popular practice here in Williams, Fernando tells me.

Decorating one's automobile seems to be a natural urge. The automotive industry has known for years that people endow their vehicles with part of their identity, and often it is a large portion. Advertising campaigns target this inclination: it's not merely a means of going from point A to point B, it's "Oh What A Feeling." In Nissan ads, the potency of their cars is enough to allow Barbie to be stolen away from a rather boring Ken. Cars, these ads seem to tell us, don't just reflect who we are, they make us who we are.

Decorating one's automobile seems to be a natural urge. The automotive industry has known for years that people endow their vehicles with part of their identity, and often it is a large portion. Advertising campaigns target this inclination: it's not merely a means of going from point A to point B, it's "Oh What A Feeling." In Nissan ads, the potency of their cars is enough to allow Barbie to be stolen away from a rather boring Ken. Cars, these ads seem to tell us, don't just reflect who we are, they make us who we are.

What the auto industry can't possibly control, however, is the absolute refusal of many individuals to have their identity created for them. Yes, we'll buy into cars as a reflection of who we are, but that image will be of our own making. José knows that, and so do others from Williams, California to Houston, Texas and beyond.

What the auto industry can't possibly control, however, is the absolute refusal of many individuals to have their identity created for them. Yes, we'll buy into cars as a reflection of who we are, but that image will be of our own making. José knows that, and so do others from Williams, California to Houston, Texas and beyond.

Houston is the site of the annual Orange Show Art Car Weekend , now in its tenth year. Here transportation becomes transformation as each vehicle explodes beyond the expected into moving sculptural forms. But these visionaries aren't the only car artists. In point of fact, most of us join their ranks: with a bumper sticker here, a graduation tassle hanging from the rearview mirror there, and other subtle ways, we seek to individualize the means of our journey.

Some styles of car decoration have become cultural markers. While some evidence suggests that Low Rider modifications were not always the signature domain of the Latino community, in many eyes it has become that. Specialty magazines attest to this, both arising out of and reflecting entire communities as well as individual artists.

The dusty and starkly beautiful art of José Sandoval also reflects his cultural affiliations. The Virgin of Guadalupe has become simultaneously a symbol of Catholicism and Latino identity. Its presence on glass reminds me the glinting beauty of Cathedral windows. The word "Aztlan" has come to hold varying meanings: to some it is the realm of the Aztecs, to some it is simply the area we are standing on, and to others it is a call for the revolutionary reclamation of the South West by Latinos.

The dusty and starkly beautiful art of José Sandoval also reflects his cultural affiliations. The Virgin of Guadalupe has become simultaneously a symbol of Catholicism and Latino identity. Its presence on glass reminds me the glinting beauty of Cathedral windows. The word "Aztlan" has come to hold varying meanings: to some it is the realm of the Aztecs, to some it is simply the area we are standing on, and to others it is a call for the revolutionary reclamation of the South West by Latinos.

When I ask José and Fernando about the term, Fernando shrugs and says "Pyramids." I leave it at that. This car means a lot to José, and that's all I really need to understand. I thank them, wave, and watch them drive away through the streets of Williams.

8/23/97

back to the main page

José Sandoval emigrated from Mexico six years ago and he's made Williams, California his home ever since. There are about two thousand people living in this little town just off Highway 20. I live in Los Angeles, where one populous suburb runs into another until expansion halts at the ocean's edge, so it's often difficult for me to remember that small communities even exist in our state. Williams can only be described as sleepy. The dust from the surrounding fields seems to float through the streets and coat the buildings with softness. The light is under a perpetual muted filter despite the relentless heat.

José Sandoval emigrated from Mexico six years ago and he's made Williams, California his home ever since. There are about two thousand people living in this little town just off Highway 20. I live in Los Angeles, where one populous suburb runs into another until expansion halts at the ocean's edge, so it's often difficult for me to remember that small communities even exist in our state. Williams can only be described as sleepy. The dust from the surrounding fields seems to float through the streets and coat the buildings with softness. The light is under a perpetual muted filter despite the relentless heat.

José's twenty now, and he gets by just fine doing agricultural work in the fields and occasionally applying his knack for working with machines. In his spare time he works on his car and hangs out with friends like Fernando Valdez, who he's known since High School. Fixing up his car is something of a burgeoning obsession for José, and he apologized sheepishly for the current dirtiness of his vehicle as I snapped away.

José's twenty now, and he gets by just fine doing agricultural work in the fields and occasionally applying his knack for working with machines. In his spare time he works on his car and hangs out with friends like Fernando Valdez, who he's known since High School. Fixing up his car is something of a burgeoning obsession for José, and he apologized sheepishly for the current dirtiness of his vehicle as I snapped away.

Decorating one's automobile seems to be a natural urge. The automotive industry has known for years that people endow their vehicles with part of their identity, and often it is a large portion. Advertising campaigns target this inclination: it's not merely a means of going from point A to point B, it's "Oh What A Feeling." In Nissan ads, the potency of their cars is enough to allow Barbie to be stolen away from a rather boring Ken. Cars, these ads seem to tell us, don't just reflect who we are, they make us who we are.

Decorating one's automobile seems to be a natural urge. The automotive industry has known for years that people endow their vehicles with part of their identity, and often it is a large portion. Advertising campaigns target this inclination: it's not merely a means of going from point A to point B, it's "Oh What A Feeling." In Nissan ads, the potency of their cars is enough to allow Barbie to be stolen away from a rather boring Ken. Cars, these ads seem to tell us, don't just reflect who we are, they make us who we are.

What the auto industry can't possibly control, however, is the absolute refusal of many individuals to have their identity created for them. Yes, we'll buy into cars as a reflection of who we are, but that image will be of our own making. José knows that, and so do others from Williams, California to Houston, Texas and beyond.

What the auto industry can't possibly control, however, is the absolute refusal of many individuals to have their identity created for them. Yes, we'll buy into cars as a reflection of who we are, but that image will be of our own making. José knows that, and so do others from Williams, California to Houston, Texas and beyond.

The dusty and starkly beautiful art of José Sandoval also reflects his cultural affiliations. The

The dusty and starkly beautiful art of José Sandoval also reflects his cultural affiliations. The